Note: The posters on the “Gender Roles” page were directed toward white women. There is an evident lack of substantive record of posters aimed toward Black women, Indigenous women, and other women of color. The same limitation applies to the “Race Thinking” page. Further research should conduct a deeper dive to excavate this information.

An Overview

After the aftermath of WWI left Germany in shambles, Hitler rose to power. WWII started when Germany invaded Poland. Other European countries soon got involved and the U.S. entered after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. The war was fought between the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) and the Allies (France, Great Britain, Soviet Union, U.S., and China). During the war, Hitler/Nazi Germany committed the Jewish Holocaust. WWII was even bloodier and deadlier than WWI.

In December 1940, Britain asked the U.S. for help against the Germans. FDR had to figure out how to convince the public that supporting Britain against Germany was a good idea. The U.S. was confident in its neutrality, so fireside chats were designed to feel like personal conversations with Americans. If Americans felt heard, they might be more receptive to getting involved in the war. Addressing the American public in a fireside chat on December 29, 1940, President Roosevelt stated “We must be the great arsenal of democracy.” With the above statement, Americans were called to action to defend not only their freedom and democracy but also democracy and freedom around the world (Europe).

Sharing the Propaganda Space

During WWII, posters were no longer the main form of propaganda, both government-issued and otherwise published. Radio and films were also mediums of propaganda.1 Even though this project focuses on posters, it is crucial to recognize that the messages in the posters were frequently supplemented by the radio and film. Further research might explore this relationship in more depth.

Race Thinking

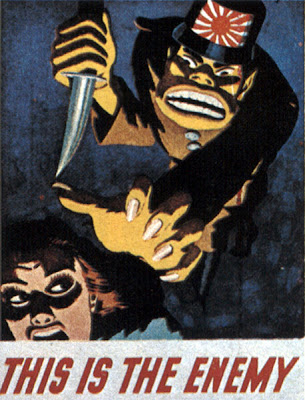

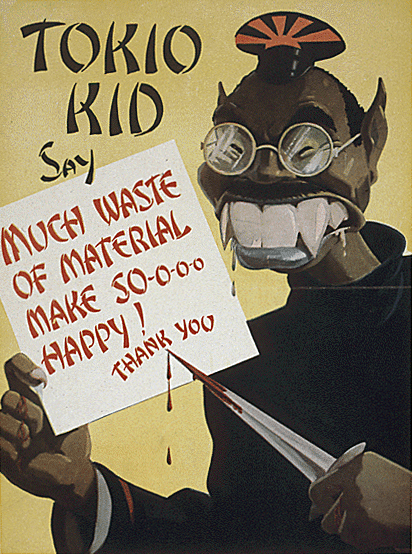

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese rhetoric and racism spiked. Anti-Asian racism had been building for quite some time, as indicated by xenophobic immigration legislation. When the U.S. joined WWII, propaganda posters depicted Japanese soldiers and civilians with animalistic and dehumanizing caricatures.23

Meanwhile, the government discouraged anti-Black racism because the U.S. was fighting the white supremacist regime of Germany. How could the war be justified if Americans believed that the U.S. was a white supremacist country itself?

“Double V” Campaign

The U.S. Government issued a series of propaganda posters with a singular V, for victory abroad. The Pittsburgh Courier, the largest Black newspaper in the country, added another V for racial equality at home.4 Other Black newspapers across the U.S. praised the Courier and added “Double V” sections to their own newspapers. Soon, pins, stickers, songs, and posters were produced as symbols of support and racial pride.

Representation of Women

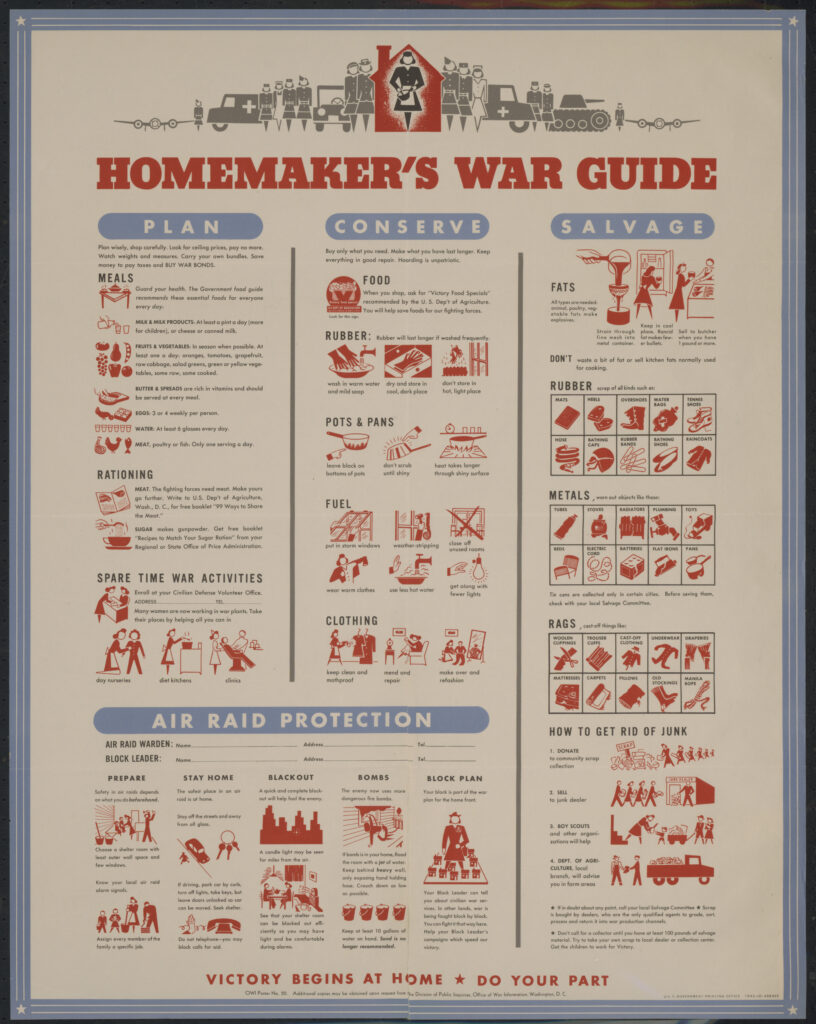

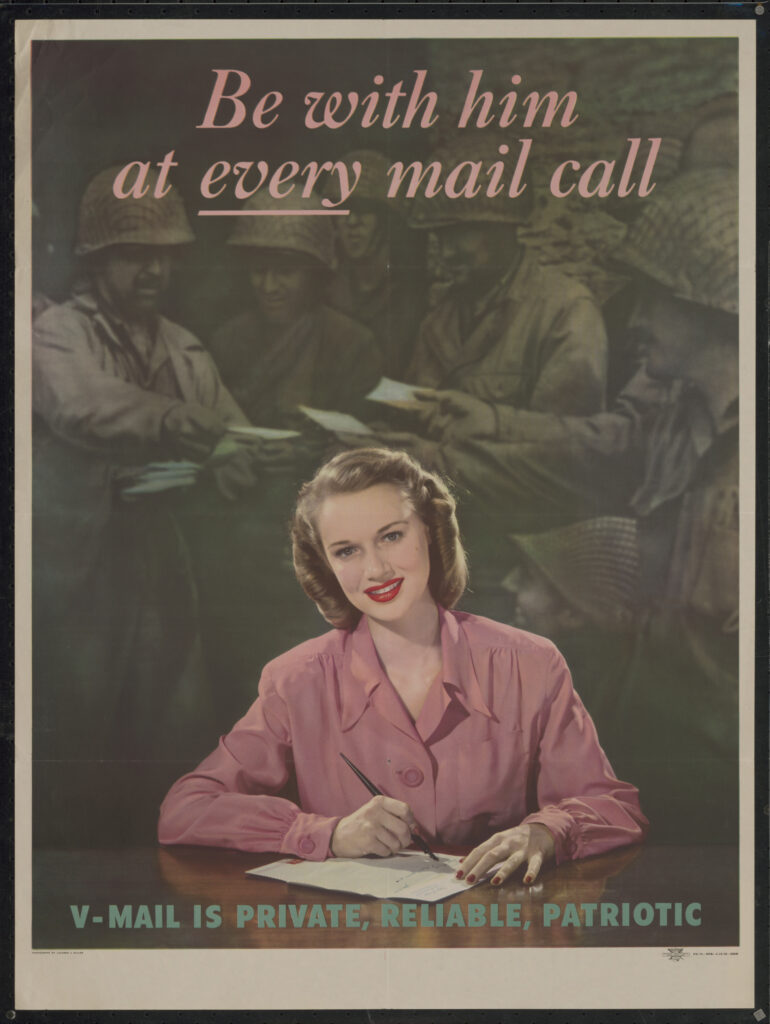

Women were still predominantly viewed as homemakers and housewives, their primary job to care for their homes, husbands, and families.5 Posters reflected this. Some instructed women on how to shift their daily routines to contribute to the war effort from their homes. Others told women that being a patriot meant supporting their husbands, by writing letters to boost morale for example.

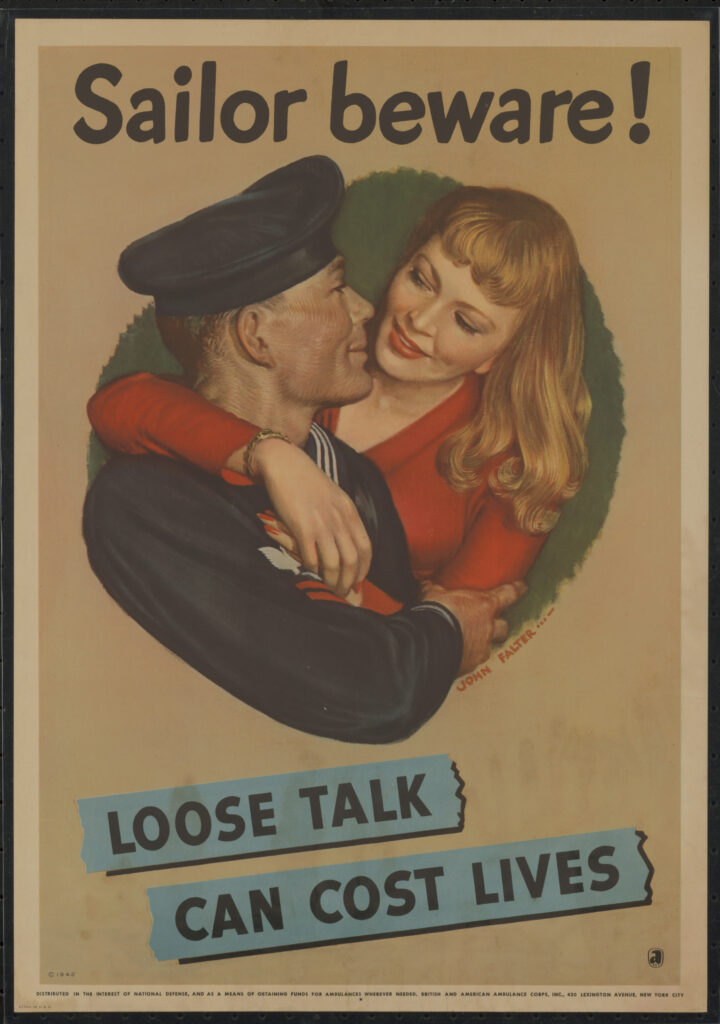

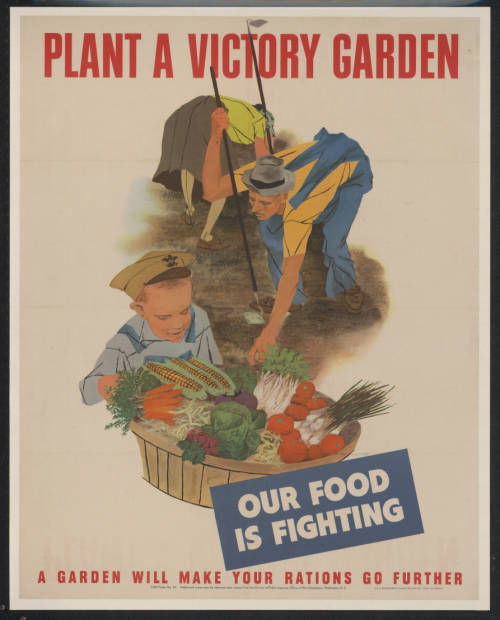

Many posters continued to sexualize women to get their point across. From “careless talk” to victory garden campaigns, posters depicted women as seductresses. They changed from immoral and untrustworthy to seemingly offering a sexual reward (depending on the context).

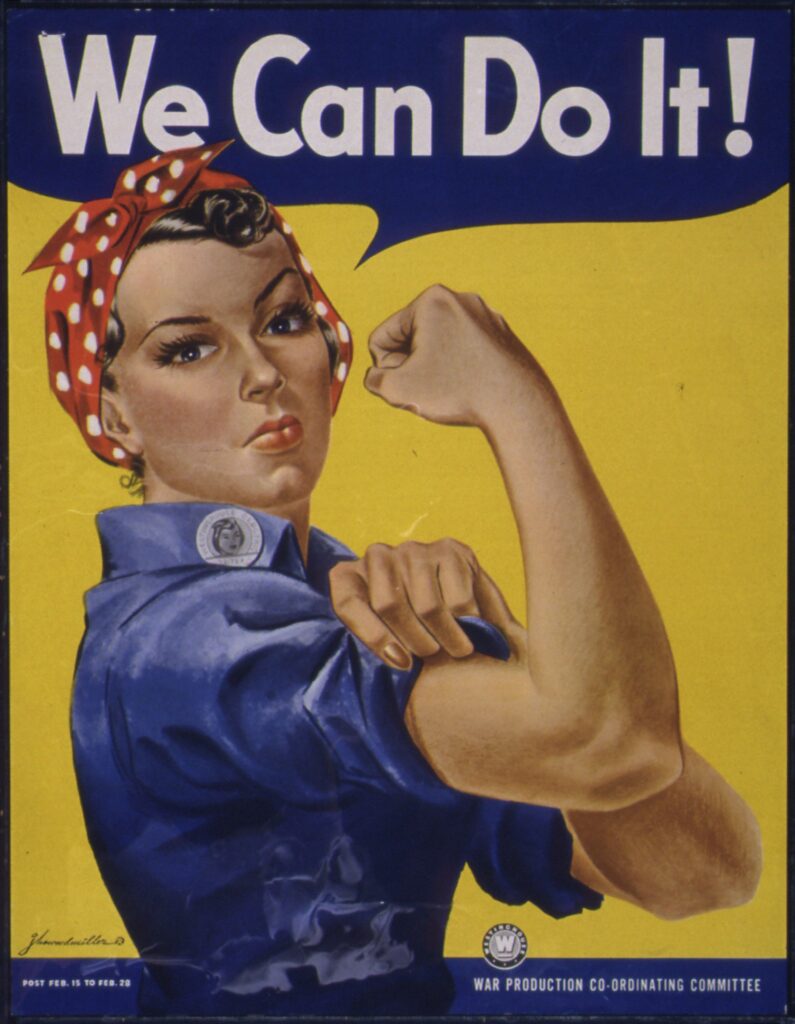

During WWII, there was a huge push to get women to work.6 7 This time, women were portrayed with their femininity (or traces of it) while they worked in different jobs. The posters during this war were more empowering for women.

Role of Economics

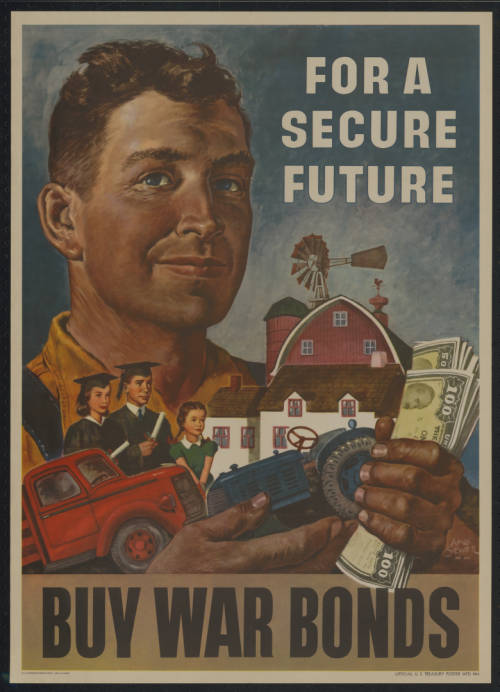

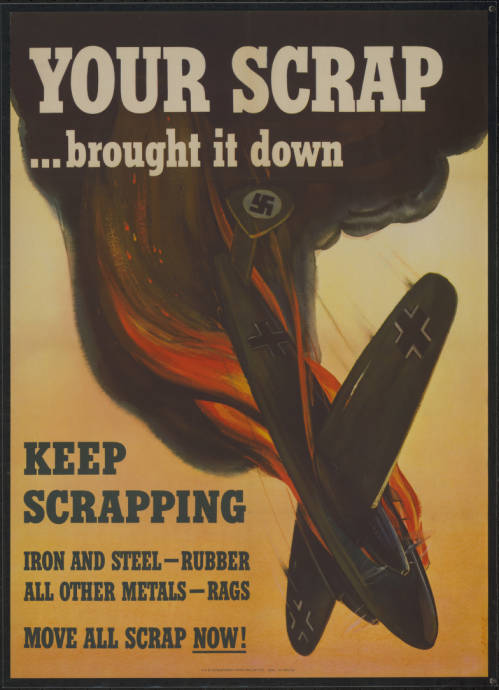

The U.S. government asked civilians for help in funding the war (war bonds), building weapons and other technologies (scrapping), and providing enough food for soldiers overseas (victory gardens). They also encouraged women to take the jobs that men left behind for war.

Like during WWI, war bonds were a way to contribute to the war effort in the present. They were also a way to invest in the future with victory at war and achieving the American Dream at home. After the end of the Great Depression, civilians started to have disposable income again. However, many industries had converted to war production so people couldn’t spend their money.6 War bonds were an outlet.

The U.S. also had to compensate for shortages in materials and food.3 Many posters were made urging civilians to donate their scraps and they would be recycled into war products. This was a way that people could directly contribute to the war effort. To address food shortages, the government advertised victory gardens, like in WWI. People would grow their own vegetables so that more food could be shipped overseas.

Posters addressed women in the workforce by removing the viewer’s sense of individuality.7 Workers, specifically women workers, were now a part of a collective and more important patriotic identity. If women believed themselves and their lives to exist outside of the cause, they would not contribute/work with the urgency of victory.

- Welch, David. World War II Propaganda Analyzing the Art of Persuasion during Wartime. ABC-CLIO, 2017. [↩]

- Welch, David. World War II Propaganda Analyzing the Art of Persuasion during Wartime. ABC-CLIO, 2017. [↩]

- Winkler, Allan M.. Home Front U. S. A. : America During World War II, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gettysburg/detail.action?docID=1765088. [↩] [↩]

- White, Steven. World War II and American Racial Politics: Public Opinion, the Presidency, and Civil Rights Advocacy. CAMBRIDGE UNIV Press, 2019. [↩]

- Honey, Maureen. Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II. The University of Massachusetts Press, 1984. [↩]

- Winkler, Allan M.. Home Front U. S. A. : America During World War II, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gettysburg/detail.action?docID=1765088. [↩] [↩]

- Honey, Maureen. Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II. The University of Massachusetts Press, 1984. [↩] [↩]