Anti-Japanese Propaganda

Anti-Japanese propaganda did not shy away from racist caricatures and ideologies. The U.S. government could not racialize the Germans as they did during World War I because the U.S. was fighting a white supremacist regime.1 As a result of accidental anti-racism from vilifying Nazi Germany, the U.S. focused its racism on the Japanese.

Anti-Japanese racism, going back to anti-Asian racism in the 1870s, then led to Japanese Internment Camps during World War II. Established by President Roosevelt in an executive order after the Pearl Harbor bombing, the government forcibly removed Japanese Americans from their homes in California, Washington, and Oregon. They were incarcerated in the Internment Camps until the end of the war in 1945.2 3

The Tokio Kid

The Tokio Kid was a recurring figure in anti-Japanese propaganda posters. Explore an example below!

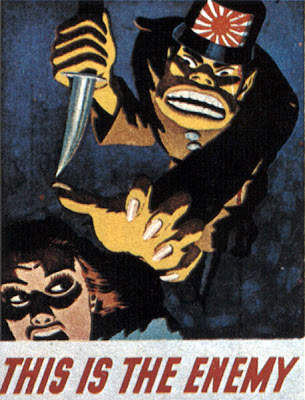

This is the Enemy – “yellow peril”

This poster stamp provides a clearer example of “yellow peril”. The Japanese figure’s skin is yellow, which is emphasized by the white woman’s peach skin tone. The Japanese figure’s menacing facial expression adds to the harsh shadows meant to evoke fear from the American viewer.

The poster stamp tells American viewers that Japan is the enemy. The attack on Pearl Harbor made the war real for many Americans since it was now on U.S. soil. The predatory attack of the Japanese soldier on the white American women preys on this development.

Citation: “This is the Enemy”, http://chumpfish3.blogspot.com/2010/03/this-is-enemy.html.

The Fight for Civil Rights: Pittsburgh Courier’s “Double V” Campaign

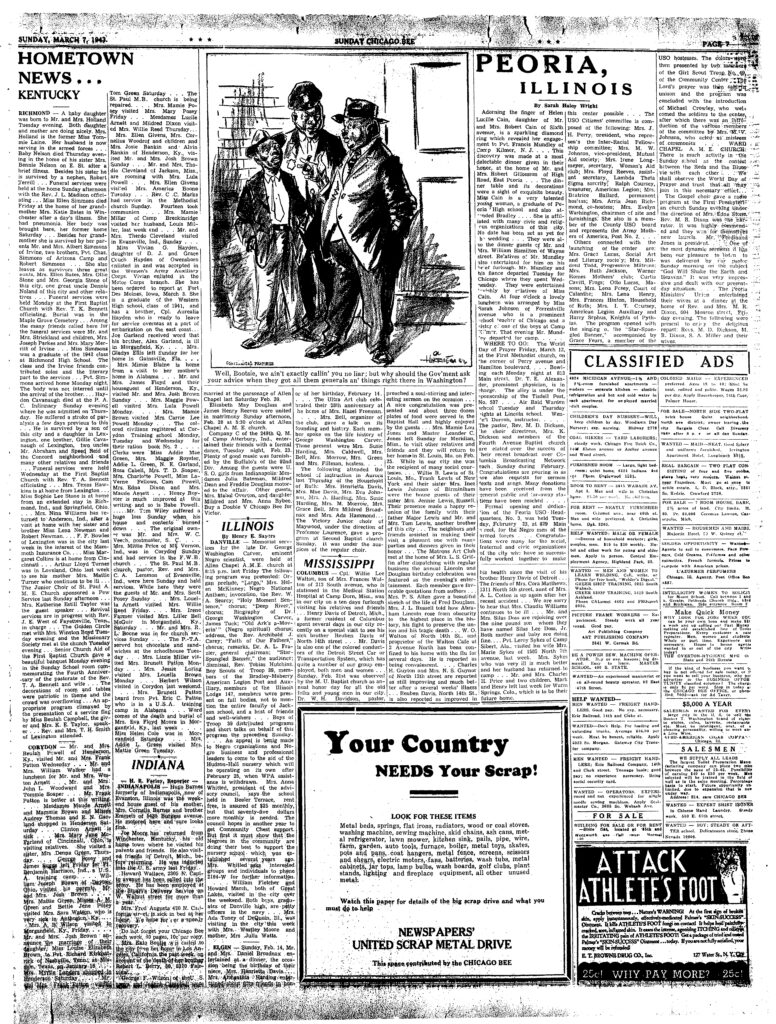

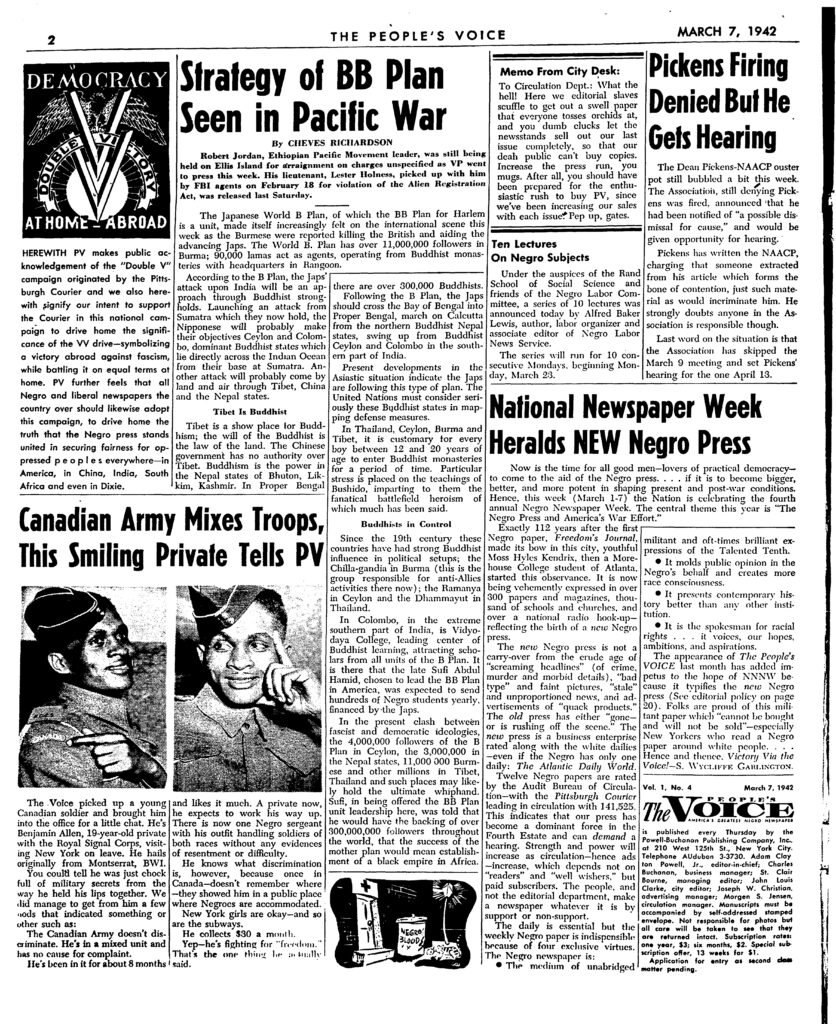

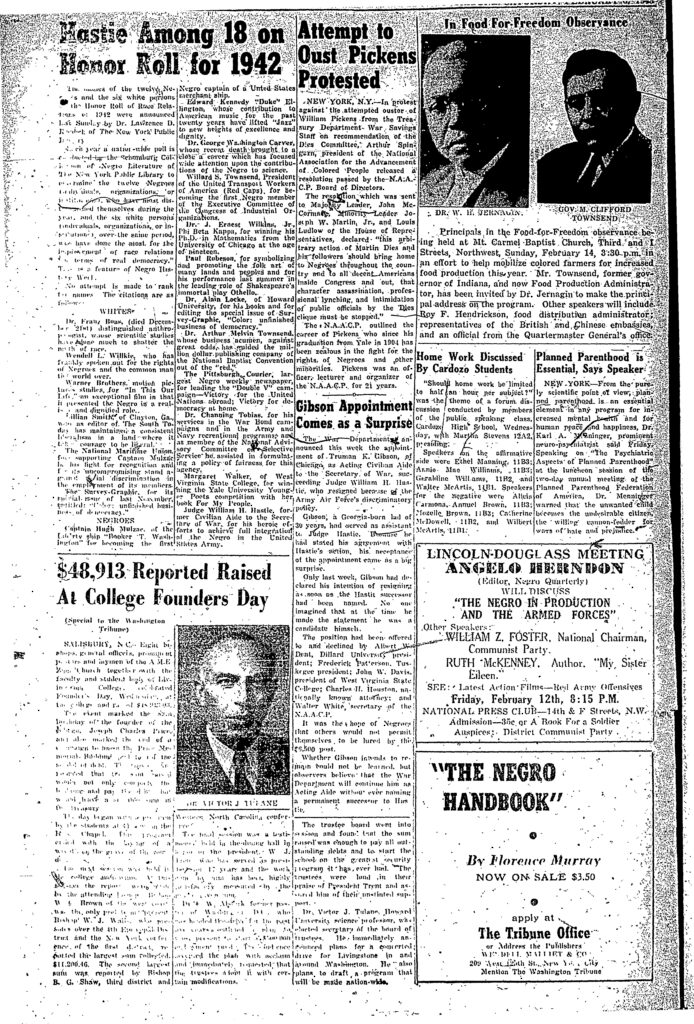

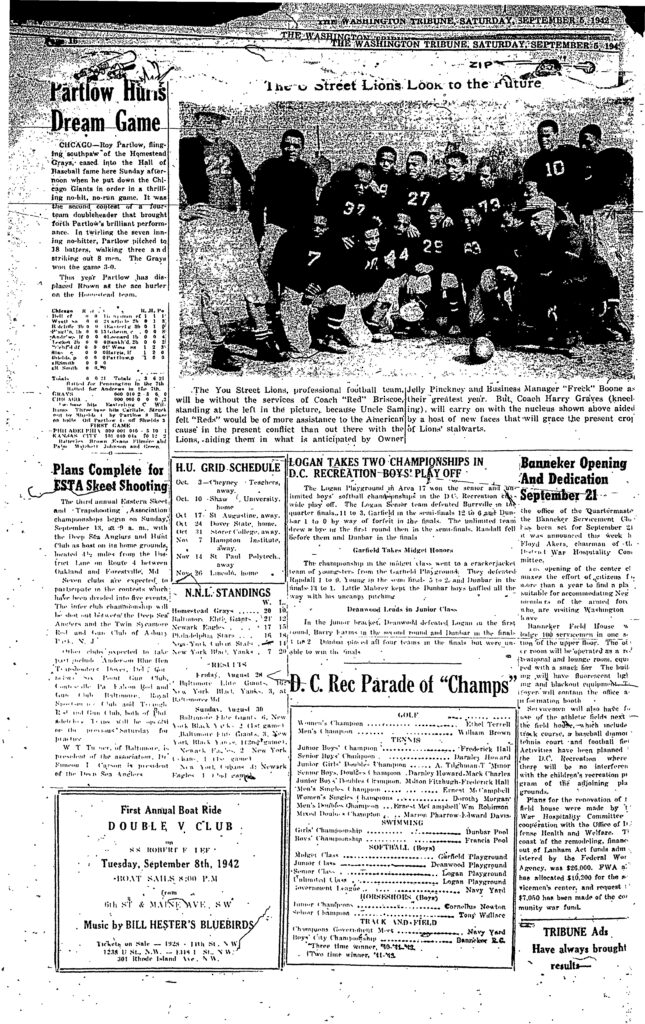

The Double V logo, the image below on the upper left, was designed by Wilbert L. Holloway, a Pittsburgh Courier staff member, in 1942. It explains that the campaign’s purpose was to fight for victory (democracy and freedom) at home and abroad.4 The U.S. Government issued a series of propaganda posters with a singular V, for victory abroad. The Pittsburgh Courier added another V for racial equality at home. Other Black newspapers across the U.S. praised the Courier and added “Double V” sections to their own newspapers. Soon, pins, stickers, songs, and posters were produced as symbols of support and racial pride.

Double V clubs saw membership skyrocket and the Pittsburgh Courier reached 2 million readers by the end of the war. But as the campaign gained more and more support, the federal government saw its success as a threat. The government eventually banned Black newspapers from the U.S. Military libraries and the FBI became involved to charge publishers with treason.

Click on an image to open in a new tab and zoom in!

Top Middle: Zoom in to the text above “Illinois”

Top Right: Zoom in to upper left corner with the Double V logo

Bottom Left: Zoom in to upper right corner article titled “Along the Battlefield”

Bottom Middle: Zoom in to upper left corner “Honor Roll”

Bottom Right: Zoom in to bottom left corner “Boat Ride” announcement

- White, Steven. World War II and American Racial Politics: Public Opinion, the Presidency, and Civil Rights Advocacy. CAMBRIDGE UNIV Press, 2019. [↩]

- Welch, David. World War II Propaganda Analyzing the Art of Persuasion during Wartime. ABC-CLIO, 2017. [↩]

- Winkler, Allan M.. Home Front U. S. A. : America During World War II, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/gettysburg/detail.action?docID=1765088. [↩]

- White, Steven. World War II and American Racial Politics: Public Opinion, the Presidency, and Civil Rights Advocacy. CAMBRIDGE UNIV Press, 2019. [↩]